Desmids in the food web

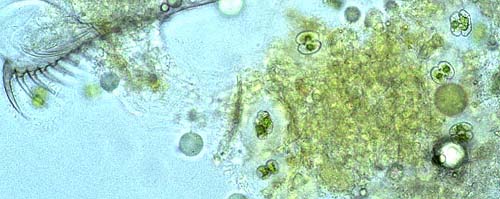

In view of the information that in the aquatic environment desmids can make a considerable part of the unicellular algal biomass they likely are important as a food source for various invertebrates. However, remarkably little scientific literature about this subject can be traced. No doubt this has to do with the fact that most research in this field is focussed on grazing of phytoplankton by zooplankton in deep, often eutrophic water bodies, for desmids the least favourable of all standing freshwater habitats. Yet, desmids have been shown to be a potential food source for zooplankters like cladocera (water fleas) and copepods. For where desmids occasionally cause an algal bloom they do have been detected in the guts of cladocera (Infante 1973). From experiments it appeared that planktonic desmid species may be well digested by daphnids, particularly if there is no protecting mucous envelope around the desmid cell, like in Staurastrum chaetoceras. In case of capsulated desmid species, like Cosmarium abbreviatum var. planctonicum, digestion is more problematic (Coesel 1997).

Mouse over images ©

Peter Coesel

Daphnia galeata fed with a culture of Cosmarium abbreviatum var. planctonicum. In the gut quite a series of intact Cosmarium cells are to be recognized.

mouse-over:

Detail of intact Cosmarium cells (protected by a mucilaginous envelope) in the gut of a Daphnia galeata specimen.

Image © Peter

Coesel

Image © Peter

Coesel

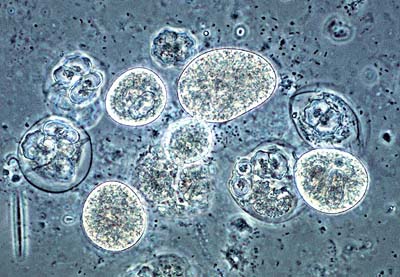

Faeces of Daphnia galeata still containing intact (live?) cells of Cosmarium.

Despite the fact that Dplanktonic desmids are a good potential food source, in practice, because of their low population density, they use to play but a minor role in the pelagial food web (at least in temperate climatic regions, for in the tropics the situation is possibly different). In contrast to that, there are numerous observations of desmids making an important component in the menu of diverse littoral animals, ranging from protozoa to fishes (Brook & Ells 1987; Coesel 1997). In particular where desmids cover the submerged substrate as a green film visible with the naked eye, they are taken up in large numbers by grazers like rotifers, midge larvae, worms etc.

Image © Michael

Dingley

A rotifer with in its gut several Closterium species.

Image ©

Alfred van Geest

Another rotifer that consumed a series of different desmids, among which a large cell of Euastrum crassum.

image © Wim

van Egmond,

The rotifer Tetrasiphon hydrocora with cells of Micrasterias rotata.

Image ©

Alfred van Geest

Image ©

Alfred van Geest

Detail of the pharynx of the same rotifer specimen in which the following desmid species can be recognized: Cosmarium amoenum, Staurastrum teliferum, Staurastrum brachiatum, Staurodesmus dejectus and Euastrum bidentatum (in lateral and apical view).

Mouse over image © Wim

van Egmond,

Mouse over image © Wim

van Egmond,

An oligochaete worm with in its gut various algal species, among which the desmid Closterium moniliferum.

An amoeba (Amoeba proteus) using two pseudopods (false feet) to capture Staurastrum brachiatum.

Image © Wim van Egmond, mouse-over

A protozoan (helizoan?) enclosing quite a number of small Actinotaenium cells.

Image © Koos Meesters

A ciliate enclosing some cells of Micrasterias truncata.

Image © Wim van Egmond

Image © Henk

Schulp, mouse-over

Cells of an unidentified amoeba together with cells of the desmid Cosmarium meneghinii.

Incidentally, cells of desmid species are encountered which are tightly enclosed by a transparent, sharply bordered envelope, about one micrometer in thickness and showing no external sculpture. Phycologists have racked their brains about the possible nature of those envelopes since a long time. According to Wasylik (1962) the most likely originator of that phenomenon would be Chlamydomyxa labyrinthuloides, an amoebe-like organism parasiting on various aquatic plants. Possibly it is identic to the organism described by Lenzenweger (1972) as an amoebe that is specialized in capturing desmids. The relatively sluggish and tough amoebe in question encloses one or more desmid cells and secretes a wall around itself. After having taken in a greater or lesser part of the content of the desmid cells the amoebe slips out, leaving behind an envelope with one or more dead, more or less empty desmid cells. Canter-Lund & Lund (1995: 260-263) picture similar digestion cysts of the amoeboid organisnm Asterocaelum, predominantly feeeding on centric diatoms.

Image © Peter

Coesel

A cell of Cosmarium quadrum encapsulated by a cyst of an unknown consumer, possibly the amoebe-like Chlamydomyxa labyrinthuloides.

For more information

and pictures see Mesotaenium macrococcum and the websites by

Bill Ells and Wim van Egmond.

References: